Richard Owen

(1804-1892)

"Owen needed a sensible alternative

to transmutation embedded in a non-materialist framework, and he too turned

to German transcendentalism, which he blended and muted with a liberal

appeal to law. Far from the sterile hybrid that Huxley would have us believe,

the union was astonishingly productive. First, it gave him the ideal Archetype,

the 'primal pattern' on which all vertebrates were based. This was a kind

of creative blueprint, "what Plato would have called the 'Divine Idea'".

In practical terms, it was simply a picture of a generalised or schematic

vertebrate; but this in itself provided him with a standard by which

to gauge the degree of specialisation of fossil life, and in 1853 he saw

it as an indispensable aid in determining the true pattern of emergence

'of new living species'."

(Adrian Desmond 1982, p. 43)

"The moral purpose

behind Owen's science is clear: to prove that Man was in the Divine Mind

at the time of Creation. Owen knew of course that not all fossil lines

pointed the human way, in fact only one of many did - still, there was

a timeless purpose behind nature's veneer. Romanticism this was, though

of a typical British variety: shadows of change masked an eternal truth,

a preordained Plan. But Owen was never one to accept the panpsychic mysticism

of the German nature-philosophers, under the influence of F. W. J. Schelling,

the Prince of Romantics. For Schelling nature was immanent in God and the

Divine Intelligence reached out to express itself through a kind of cosmic

poetry. Owen denied that the 'Great Cause of all ' was an 'all-pervading

anima

mundi', the more pointedly, perhaps, because Schelling had actually

pleaded guilty to a sort of pantheism, and Owen himself had been accused

of it by Puseyites. Rather, his God was a traditional British craftsman

working to a blueprint."

(Adrian Desmond 1982, p. 47-48)

"The Archetype is progressively departed from as

the organization is more and more modified in adaptation to higher and

more varied powers and actions."

(Richard Owen 1849a)

"I believe ... that I have satisfactorily

demonstrated that a vertebra is a natural group of bones... and that the

parts of that group are definable and recognizable under all their teleological

modifications, their essential relations and characters appearing through

every adaptive mask."

(Richard Owen 1849a)

"General anatomical science reveals

the unity which pervades the diversity, and demonstrates the whole skeleton

of man to be the harmonized sum of a series of essentially similar segments,

although each segment differs from the other, and all vary from their archetype."

(Richard Owen 1849a)

"The conceivable modifications of

the vertebrate archetype are very far from being exhausted by any of the

forms that now inhabit the earth, or that are known to have existed here

at any period... The discovery of the vertebrate archetype could not fail

to suggest to the Anatomist many possible modifications of it beyond those

that we know to have been realized in this little orb of ours."

(Richard Owen 1849a)

"To what natural laws or secondary

causes the orderly succession and progression of such organic phenomena

may have been committed we as yet are ignorant. But if, without derogation

of the Divine power, we may conceive the existence of such ministers, and

personify them by the term 'Nature', we learn from the past history of

our globe that she has advanced with slow and stately steps, guided by

the archetypal light, amidst the wreck of worlds, from the first embodiment

of the Vertebrate idea, under its old Ichthyic vestment, until it became

arrayed in the glorious garb of the human form."

(the closing paragraph of Richard Owen's

(1849a) address, On the nature of limbs,

delivered to the Royal Institution of Great Britain and

published in 1849,

all from Gould 1986b)

"Organic remains, traced from their

earliest known graves, are succeeded, one series by another, to the present

period, and never reappear when once lost sight of in the ascending search.

As well might we expect a living Ichthyosaur in the Pacific, as a fossil

whale in the Lias: the rule governs strongly in the retrospect as the prospect.

And not only as respects the Vertebrata, but the sum of the animal species

at each successive geological period has been distinct and peculiar to

each period."

(against the doctrine of the Uniformitarian

of Sir Charles Lyell,

Richard Owen 1860b, p. 410-411)

"In regard to animal life, and its

assigned work on this planet, there has.. plainly been 'an ascent and progress

in the main'."

(arguing for progress, Richard Owen 1860b,

p. 411)

"Our most soaring speculations still

show a kinship to our nature; we see the element of finality in so much

that we have cognizance of, that it must needs mingle with our thoughts

and bias our conclusions on many things.

The end of the world has been presented to man's

mind under divers aspects: as a general conflagration; as the same, preceded

by a millenial exaltation of the world to a paradisiacal state, - the abode

of a higher race of intelligences.

If the guide-post of Palaeontology may seem to

point to a course ascending to the condition of the latter speculation,

it points but a very short way, and in leaving it we find ourselves in

a wilderness of conjecture, where to try to advance is to find ourselves

'in wandering mazes lost'."

(on finality, Richard Owen 1860b, p. 412)

"Everywhere in organic nature we see

the means not only subservient to an end, but that end accomplished by

the simplest means. Hence we are compelled to regard the Great Cause of

all, not like certain philosophic ancients, anima mundi, but as

an active and anticipating intelligence."

(on the Creative Power, Richard Owen 1860b,

p. 413)

"Hence we not only show intelligence

evoking means adapted to the end; but, at successive times and periods,

producing a change of mechanism adapted to a change in external conditions.

Thus the highest generalizations in the science of organic bodies, like

the Newtonian laws of universal matter, lead to the unequivocal conviction

of a great First Cause, which is certainly not mechanical."

(concluding remark of the book Palaeontology,

Richard Owen 1860b, p. 414)

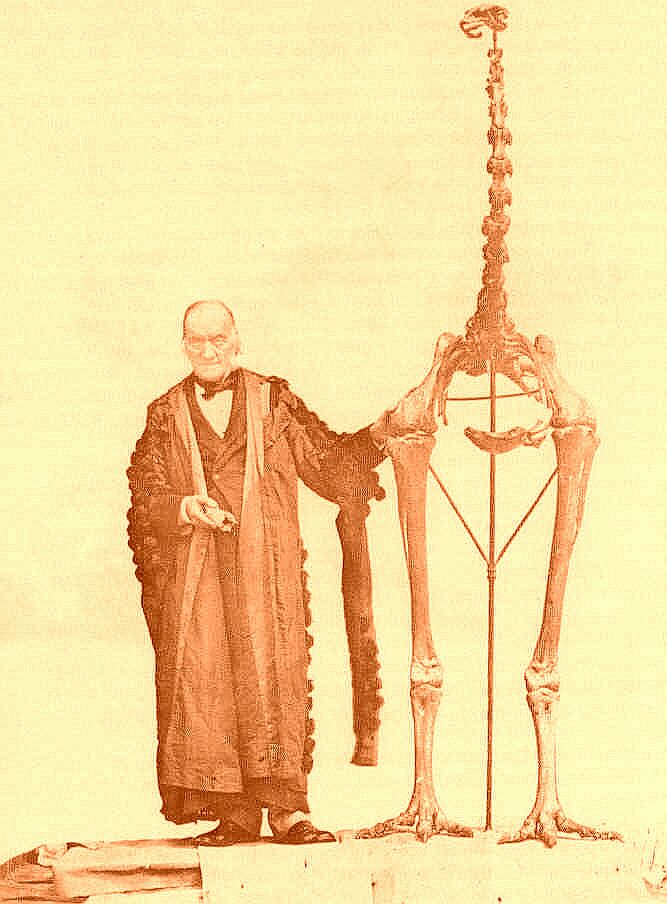

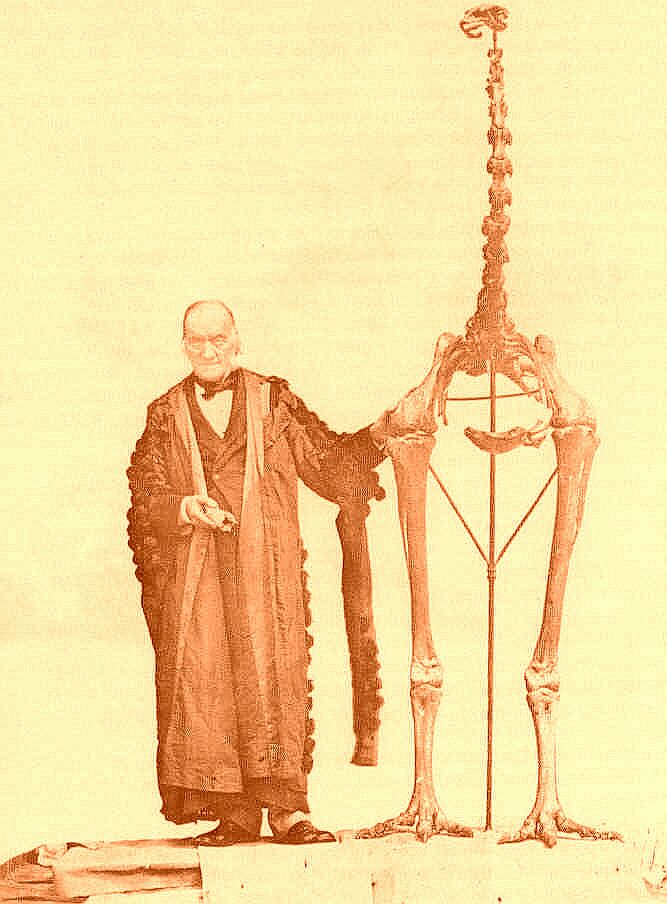

Richard Owen with a skeleton of Dinornis torosus HUTTON,

1891;

in his right hand Owen holds the most important bone found by John

Rule,

first moa relic that came to the attention of scientists;

in 1839 Owen announced that giant ostrich-like birds once inhabited

New Zealand

(or even perhaps at that time still lived)...

Go to the bibliography of Richard

Owen