The Fossil Heritage Collection

Stephanoura belgica

Ubaghs, 1941. Late Devonian age. Velbert, Langenhorst, Germany. MPRI 0008. Preserved as a mould. Despite its great age it is legitimately assigned to the living family Ophiolepididae. Not previously represented in North American institutional collections. Supports the research theme Paleozoic ophiuroids of modern aspect. References: Ubaghs 1941, 1953; Thomas 1979; Haude & Thomas 1983; Hotchkiss & Haude 2004. Photo by Faith Margolin.

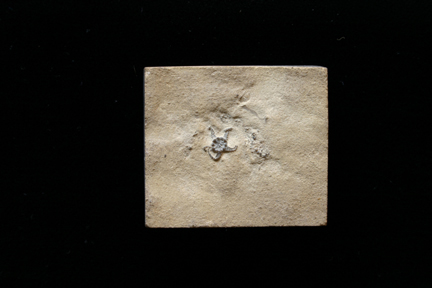

Salteraster wilsonae

(Raymond 1912) new comb. Middle Ordovician Bobcaygeon Formation. Carden Quarry, near Brechin, Ontario, Canada. Collected and prepared by Bill Hessin, Hastings, Ontario. MPRI 0001. Partly solid calcite, and partly a mould. This species previously was assigned to the genus Promopalaeaster. In 1975 Branstrattor reidentified Promopalaeaster wilsoni as Salteraster huxleyi (Billings) but did not explain his reasons. Transfer to the genus Salteraster and family Urasterelldae is accepted. However, because there is a significant age difference between S. huxleyi [Chazyan age (older)] and "P. wilsoni" [Leray-Rocklandian age (younger)], it seems best to use the new combination S. wilsonae until the possible synonymy with S. huxleyi can be investigated as a future research project. The spelling is changed from the masculine "wilsoni" to the feminine "wilsonae" because the species is named for Alice E. Wilson. Supports the research theme "Ordovician Biodiversity". References: Raymond 1912; Wilson 1946; Branstrattor 1975; Kolata 1975; Brett & Rudkin 1977; Hotchkiss et al. 1997; Rudkin et al. 1997. Photo by Faith Margolin.

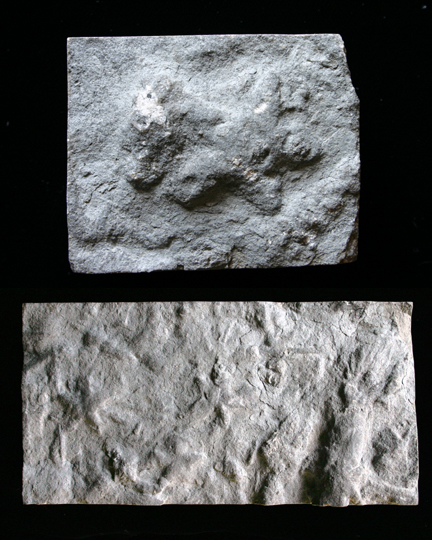

Asteriacites sp.

Middle Ordovician. North wall of Carden Quarry, near Brechin, Ontario, Canada. Two slabs collected and donated by Doug McAvoy, Commanda, Ontario. MPRI 0007. Trace fossils are the result of animal activity such as walking, digging, burrowing, etc., related to feeding, resting, hiding, etc., and are described as ichnotaxa. Asteriacites is the digging trace of a starfish or an ophiuroid. Ordovician Asteriacites are not common. This may be only the second known Ordovician occurrence in North America and the first from Canada. A possible trace maker for this specimen is the primitive ophiuroid Stenaster obtusus which is found in this quarry but not directly associated with these traces. This occurrence has not yet been reported in the literature. Related literature: Miller & Dyer 1878; Seilacher 1953; Osgood 1970; Mikulas 1990; West & Ward 1990; Mangano et al. 1999. Photo by Faith Margolin.

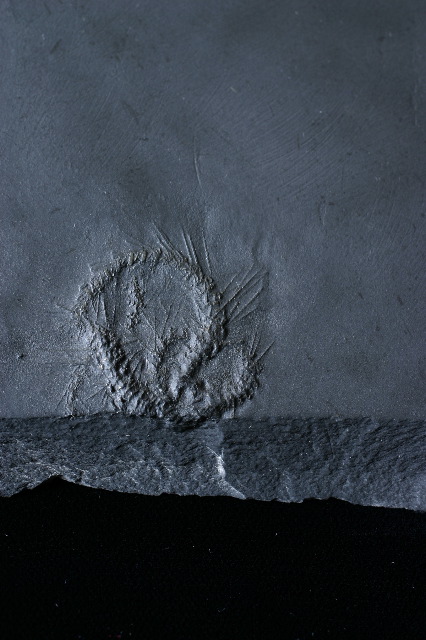

Asteriacites sp.

Mississippian, Middle Chesterian, Bangor Limestone. Colbert County, Alabama. MPRI 0074. Collected by Richard Keyes, Huntsville, Alabama. Asteriacites is the digging trace of a starfish or an ophiuroid. The shape of the trace seems to imply the thin arms and small disk of an ophiuroid as the trace maker. This occurrence has not yet been reported in the literature. Related literature: Y. Ishida, T. Fujita and K. Kamada. 2004. Ophiuroid trace fossils in the Triassic of Japan compared to the resting behavior of extant brittle stars. Pp. 433-438 In Echinoderms: Munchen -- Heinzeller & Nebelsick (eds.), Taylor & Francis Group, London. Photo by Richard Keyes.

Aspiduriella scutellata

Triassic, Germany. MPRI 0004. Triassic ophiuroids are either survivors from the Permian or are newly evolved from some ancestor that survived the Permo-Triassic extinction event. In either case they shed light on the early history and subsequent diversification that led to all the living families of ophiuroids. Literature: BOLETTE, D. P. 1998 Aspiduriella nom. n. for the genus Aspidura Agassiz, 1835 (ECHINODERMATA: OPHIUROIDEA: OPHIURIDAE); preoccupied by Aspidura Wagler, 1830 (REPTILIA: SERPENTES: COLUBRIDAE) Journal of Paleontology Vol. 72, No. 2, pp. 401–402. HAGDORN, H. 1999: Triassic ophiuroids (Aspiduriella) brooding in an empty ceratite shell. – In: CANDIA CARNEVALI & BONASORO [eds.], Echinoderm Research 1998: 278; Rotterdam, Balkema. Photo by Faith Margolin. Links: trias-verein; palaeo-online

MPRI 0002

Three images of fossil stelleroids from the Ordovician rocks of Hueston Woods State Park, Preble and Butler Counties, Ohio. Specimens in the top photo appear to be Petraster speciosus. Specimens in the middle and lower photo are not yet identified. The late Bill White, a much respected member of the Cincinnatti Dry Dredgers, discovered a crinoid and starfish pocket at Hueston Woods that is now deposited at Miami University. Literature: Ohio Division of Parks and Recreation, 1967, Fossils of Hueston Woods, 16 pp. Photo by Faith Margolin.Photo by Alexander Glass

MPRI 0003 (1 of 6 views)

Encrinaster roemeri (Schoendorf, 1910). Lower Devonian, Hunsrück Slate, Bundenbach, Germany. MPRI 0003. An unusual and historic small slab of Hunsrück Slate that is crowded with a mass occurrence of small specimens of the ophiuroid Encrinaster roemeri. The specimens are pyritised. In places the pyrite has broken out of the matrix and left a mould. Slab dimensions are about 9 1/2" long, 5/16" thick and the width varies from 1" to 1 1/2". On the front surface of the slab a handwritten label reads "Ophiuren/ Aspidosoma/ Tishbeinianum R/ U. Devon. Bundenbach." On the back surface of the slab a glued pre-printed label reads "This label was written in April 1889 by B. Stürtz, ofPhoto by Alexander Glass

MPRI 0003 (2 of 6 views)

Bonn, Germany, from whom this specimen was obtained. Wm. F. E. Gurley." Identification as Aspidosoma tischbeinianum represented the knowledge of the time. Not until 1910 was the species Aspidosoma roemeri distinguished from A. tischbeinianum. The present names are Encrinaster roemeri (Schoendorf) and Euzonosoma tischbeinianum (Roemer).William Frank Eugene Gurley was born 5 June 1854 and died 27 June 1943 [source for this paragraph is Cleevely 1983]. He was a civil engineer and one of the original Fellows of the Geological Society of America. He exchanged fossils with several leading paleontologists of his time and also supplied

Photo by Alexander Glass

MPRI 0003 (3 of 6 views)

fossils to the British dealer Damon and the Imperial Museum in Vienna. Gurley specimens are in the Muséum d'histoire naturelle de Genève, Switzerland (Decrouez 1986). Gurley was the first curator of the Illinois State Museum (Springfield) and the Illinois State Geologist from 1893-1897. From 1900 to 1943 he was Associate Curator of the Walker Museum in the Department of Geology at the University of Chicago. At 43 years of age Gurley became totally blind as a result of a childhood illness.The Gurley collection of Paleozoic invertebrate fossils was given to the University of Chicago and later transferred to

Photo by Alexander Glass

MPRI 0003 (4 of 6 views)

the Field Museum of Natural History (Chicago). The collection includes pyritised stelleroids on slabs of Hunsrück Slate with similar hand-written labels and the same pre-printed Gurley label. In May 2006 this specimen was donated by MPRI to the Yale University Peabody Museum of Natural History (YPM), where it is now cataloged as YPM 212897. The YPM is a magnet institution for scientists working on Paleozoic stelleroids thanks to the legacy of Charles Schuchert. In addition, the YPM is active in electronically cataloguing their collections and a leader in providing web access with search capability to their catalog.Kutscher (1970) mentions a mass occurrence of Encrinaster roemeri in the Hunsrück Slate, and it is possible that MPRI 0003 is part of this well-known mass occurrence (Glass, thesis, 2006). The mass occurrence is reasonably construed as the remains of a dense living assemblage. Aronson (1989) and others have postulated

Photo by Alexander Glass

MPRI 0003 (5 of 6 views)

that the rise of durophagous predators during the Mesozoic Marine Revolution should be reflected in a decline in the frequency of dense ophiuroid beds from the Paleozoic going into the Mesozoic and to present times.Details of references are in the Bibliography of Paleozoic Asterozoa in the MPRInstitute.org on-line library. Taxonomic and Hunsrück Slate references: Lehmann 1957; Kutscher 1970. Biography of Stürtz: Langer 1994. Gurley collection and biography: Proc. Geol. Soc. Amer., 1943:135-40; Cleevely 1983; Decrouez, D. 1986. Les collections du Départment de géologie et de paléontologie des invertébrés du Muséum d'histoire

MPRI 0003 (6 of 6 views)

naturelle de Genève. 22: Les collections F. Braun, deLaFontaine, W. Farren, Germain, W. F. E. Gurley et A. B. Wetherby. Rev. Paléobiol. 5(2):395-401. Mesozoic marine revolution: Aronson & Sues (1987), Aronson (1989, 2001).Photo by Alexander Glass

MPRI 0018

Eospondylus primigenius (Sturtz). Lower Devonian, Hunsrück Slate, Eschenbach-Bocksberg quarry, Bundenbach, Germany. Collected and prepared by W. H. Südkamp. Prepared further by Dr. Alexander Glass. Oral view of specimen with ventral arm enrollment. In September 2005 this specimen was donated by MPRI to the Narodni Museum, Prague, where it is cataloged as NM S4764. Photo by Faith Margolin.

MPRI 0019

Eospondylus primigenius (Sturtz). Lower Devonian, Hunsrück Slate, Eschenbach-Bocksberg quarry, Bundenbach, Germany. Collected and prepared by W. H. Südkamp. Oral view of specimen with aboral arm flexure. In September 2005 this specimen was donated by MPRI to the Narodni Museum, Prague, where it is cataloged as NM S4765. Photo by Faith Margolin.

MPRI 0020

Eospondylus primigenius (Sturtz). Lower Devonian, Hunsrück Slate, Eschenbach-Bocksberg quarry, Bundenbach, Germany. Two specimens on one slab. Collected and prepared by W. H. Südkamp. The larger specimen provides good ventral views of the arm vertabrae where the lateral arm plates are widely separated. Groove spines are present but require examination with a microscope. In September 2005 this specimen was donated by MPRI to the Narodni Museum, Prague, where it is cataloged as NM S4766. Photo by Faith Margolin.

MPRI 0021

Eospondylus primigenius (Sturtz). Lower Devonian, Hunsrück Slate, Bundenbach, Germany. Prepared by Dr. Stefan Antons. Partial specimen approximately 136 mm x 38 mm size. Aboral view. Displays extreme horizontal arm bending. In September 2005 this specimen was donated by MPRI to the Narodni Museum, Prague, where it is cataloged as NM S4767. Photo by Faith Margolin.

MPRI 0022

Eospondylus primigenius (Sturtz). Lower Devonian, Hunsrück Slate, Bundenbach, Germany. Prepared by Dr. Stefan Antons. Partial specimen with aboral view of mouth frame. In September 2005 this specimen was donated by MPRI to the Narodni Museum, Prague, where it is cataloged as NM S4768. Photo by Faith Margolin.MPRI 0023 -- MPRI 0037, also MPRI 0053, 0054 and 0072

MPRI 0023 – MPRI 0037. Fifteen small pieces of a Late Pliocene fossil brittlestar coquina bed. Tirabuzon Formation, Corkscrew Hill, north of Santa Rosalia, Northern Baja, California Sur, Mexico. The ophiuroid is unidentified and the ophiuroid bed has not been reported in the literature. Additional pieces are in the Florida State Museum (Dr. Portell, curator). Dense ophiuroid beds are of special interest because of the studies and papers by Richard Aronson who examined whether the prevalence of such beds declined from the Paleozoic to the Mesozoic as an indicator test of the influence of the Mesozoic marine revolution. This revolution is seen as the rise of durophagous marine predators and the consequent effects on the biota. Aronson et al. described a Bahamian salt water pond that had no fish predators living in it. In this pond the ophiuroids lived boldly out in the open both day and night. In the adjoining sea the same ophiuroid is exposed to fish predation and lives concealed. The specimens have been sent to graduate student René A. Lewis, Earth Sciences Department, University of North Carolina at Wilmington, for use in her master's thesis research under Prof. Patricia H. Kelley. At the conclusion of her research the material will be put into the permanent collection of an appropriate institutional repository.

MPRI specimens 0053, 0054 and 0072 of ophiuroid coquina [ophiuroid limestone] from the Santa Margarita Formation, Miocene, California. In January 2007 donated by MPRI to the Peabody Museum of Natural History, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut, and cataloged as YPM 220618-220626. Details are given below.

Dense ophiuroid beds are of special interest as explained above, and documentation of ophiuroid beds is essential to such studies. Merriam (1931) documented a brittlestar limestone up to one foot thick in the lower part of the Santa Margarita Formation. The preservation did not permit identification, making the noncommittal appellation Ophiurites appropriate. Arnold (1908) described Amphiura sanctaecrucis from this formation, and this appellation is found on MPRI 0072. The appellation Amphiura? is on the website of the Humboldt State University Natural History Museum. Blake & Allison (1970) described a block of ophiuroid limestone composed of Ophiocrossota baconi (?) from the Middle Miocene upper Branch Canyon Formation, California. The species determination was changed to O. oweni by Blake (1975).

Details of specimens MPRI 0053, 0054, 0072:

MPRI 0053. Miocene brittlestar coquina fossil. Three slices of ophiuroid coquina approximately 3 to 4 inch size. Labeled Ophiocrossota baconi Blake & Allison, Santa Margarita Formation, Miocene, Arroyo Grande Canyon, San Louis Obispo County, California. Purchased from Geological Enterprises, Inc., Ardmore, Oklahoma. [More likely O. oweni than O. baconi]. In January 2007 donated by MPRI to the Peabody Museum of Natural History, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut, where the slices are cataloged as YPM 220623-220625.

MPRI 0054. Miocene brittlestar coquina fossil. Five slices of coquina approximately 4 to 5 inch size. Labeled Ophiocrossota baconi Blake & Allison, Santa Margarita Formation, Miocene, Arroyo Grande Canyon, San Louis Obispo County, California. Purchased from Geological Enterprises, Inc., Ardmore, Oklahoma. [More likely O. oweni than O. baconi]. In January 2007 donated by MPRI to the Peabody Museum of Natural History, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut, where the slices are cataloged as YPM 220618-220622.

MPRI 0072. Miocene brittlestar coquina fossil. Labeled Amphiura sanctaecrucis from the Miocene, Santa Margarita Formation, Santa Maria, California. Purchased from Catherine Curtis & Richard D. L. Fulton, Perkasie, PA; donated by FHC Hotchkiss [More likely O. oweni than A. sanctaecrucis]. In January 2007 donated by MPRI to the Peabody Museum of Natural History, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut, where the slab is cataloged as YPM 220626.

More occurrence information from Dr. Christian C. Finch, Hillsborough Community College, Tampa, Florida: Specimens 0053 and 0054 may be from material collected by C.C. Finch, Mike McGinnis and Ralph Bishop in the late 1960's and traded to Geological Enterprises. They collected from outcrops of the Phoenix member of the late Miocene Santa Margarita Formation on the east side of the Huasna syncline, as mapped by summer geology students at UCLA (see map and localities 4170, 4171 and 4172 in Hall 1962). Specimen 0072 from Santa Maria should be from the same location, and may have been traded or sold by Ralph Bishop when he lived in Santa Maria. "The surrounding rock is medium to coarse grained sandstone with typical shallow water species such as Astrodapsis and massive Crassostrea titan which occurs in situ, upright instead of flat-lying like mst oysters. The ophiuroids are so dense that the 1-2 foot thick layer could be described as a sandy limestone; some of the lime cementing the grains is redeposited from the ophiuroid tests. The ophiuroid layer includes larger starfish, up to 4 inches across, that have not been determined."

MPRI 0053, 0054, 0072 related references: Arnold, R. 1908. Description of a new brittle-star from the upper Miocene of the Santa Cruz Mountains, California. Proceedings of the U.S. National Museum 34:403-406; Aronson, R. B. 1987. Predation on fossil and Recent ophiuroids. Paleobiology, vol. 13, no. 2, pp. 187?192; Aronson, R. B. 1987. A murder mystery from the Mesozoic.??New Scientist, 8 October 1987, pp. 55?59; Aronson, R. B. 1989. A community?level test of the Mesozoic marine revolution theory. Paleobiology, vol. 15, no. 1, pp. 20?25; Aronson, R. B. 1989. Brittle-star beds: low-predation anachronisms in the British Isles. Ecology 70(4):856-865; Aronson, R. B. 1991. An octopus’s garden. Natural History 1991(2):30-37; Aronson, R. B. 1991. Predation, physical disturbance, and sublethal arm damage in ophiuroids: a Jurassic-Recent comparison. Marine Ecology Progress Series 74:91-97; Aronson, R. B. 1992. Biology of a scale?independent predator?prey interaction. Marine Ecology Progress Series, vol. 89, pp. 1?13. [Data on proportion of individuals bearing 1 or more regenerating arms in dense, fossil ophiuroid populations. Expanded list of "fossil dense, autochthonous, shallow?water brittlestar beds"]; Aronson, R. B. 2001. Durophagy in marine organisms. pp. 393-397 In D.E.G. Briggs & P.R. Crowther (eds.), Palaeobiology II. Blackwell Science Ltd, 583 pp.; Aronson, R. B. and D. B. Blake. 1997. Evolutionary paleoecology of dense ophiuroid populations. -- Paleontological Society Papers 3:107-119; Aronson, R. B. and C. A. Harms. 1985. Ophiuroids in a Bahamian saltwater lake: The ecology of a Paleozoic?like community. Ecology, vol. 66, no. 5, pp. 1472?1483; Aronson, R. B. and H.?D. Sues. 1987. The paleoecological significance of an anachronistic community. Pp. 355?366. In Predation: direct and indirect impacts on aquatic communities. [W. C. Kerfoot and A. Sih, eds.] University Press of New England, Hanover, NH; Aronson, R. B. and H.?D. Sues. 1988. The fossil record of brittlestar beds. Pp. 147?148. In Echinoderm Biology (Proc. 6th IEC, Victoria/23?28 August 1987), [R. D. Burke et al. (eds)] A. A. Balkema, Rotterdam; Blake, D. B. 1975. A new west American Miocene species of the modern Australian ophiuroid Ophiocrossota. Journal of Paleontology 49(3):501-507; Blake, D. B. and R. C. Allison. 1970. A new west American Eocene species of the Recent Australian ophiuroid Ophiocrossota. Journal of Paleontology 44(5):925-927; Hall, C.A. 1962. Evolution of the echinoid genus Astrodapsis. University of California Publications in Geological Sciences 40(2):47-180; Merriam, C.W. 1931. Notes on a brittle-star limestone from the Miocene of California. American Journal of Science 21:304-310.

Dense ophiuroid beds are of special interest as explained above, and documentation of ophiuroid beds is essential to such studies. Merriam (1931) documented a brittlestar limestone up to one foot thick in the lower part of the Santa Margarita Formation. The preservation did not permit identification, making the noncommittal appellation Ophiurites appropriate. Arnold (1908) described Amphiura sanctaecrucis from this formation, and this appellation is found on MPRI 0072. The appellation Amphiura? is on the website of the Humboldt State University Natural History Museum. Blake & Allison (1970) described a block of ophiuroid limestone composed of Ophiocrossota baconi (?) from the Middle Miocene upper Branch Canyon Formation, California. The species determination was changed to O. oweni by Blake (1975).

Details of specimens MPRI 0053, 0054, 0072:

MPRI 0053. Miocene brittlestar coquina fossil. Three slices of ophiuroid coquina approximately 3 to 4 inch size. Labeled Ophiocrossota baconi Blake & Allison, Santa Margarita Formation, Miocene, Arroyo Grande Canyon, San Louis Obispo County, California. Purchased from Geological Enterprises, Inc., Ardmore, Oklahoma. [More likely O. oweni than O. baconi]. In January 2007 donated by MPRI to the Peabody Museum of Natural History, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut, where the slices are cataloged as YPM 220623-220625.

MPRI 0054. Miocene brittlestar coquina fossil. Five slices of coquina approximately 4 to 5 inch size. Labeled Ophiocrossota baconi Blake & Allison, Santa Margarita Formation, Miocene, Arroyo Grande Canyon, San Louis Obispo County, California. Purchased from Geological Enterprises, Inc., Ardmore, Oklahoma. [More likely O. oweni than O. baconi]. In January 2007 donated by MPRI to the Peabody Museum of Natural History, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut, where the slices are cataloged as YPM 220618-220622.

MPRI 0072. Miocene brittlestar coquina fossil. Labeled Amphiura sanctaecrucis from the Miocene, Santa Margarita Formation, Santa Maria, California. Purchased from Catherine Curtis & Richard D. L. Fulton, Perkasie, PA; donated by FHC Hotchkiss [More likely O. oweni than A. sanctaecrucis]. In January 2007 donated by MPRI to the Peabody Museum of Natural History, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut, where the slab is cataloged as YPM 220626.

More occurrence information from Dr. Christian C. Finch, Hillsborough Community College, Tampa, Florida: Specimens 0053 and 0054 may be from material collected by C.C. Finch, Mike McGinnis and Ralph Bishop in the late 1960's and traded to Geological Enterprises. They collected from outcrops of the Phoenix member of the late Miocene Santa Margarita Formation on the east side of the Huasna syncline, as mapped by summer geology students at UCLA (see map and localities 4170, 4171 and 4172 in Hall 1962). Specimen 0072 from Santa Maria should be from the same location, and may have been traded or sold by Ralph Bishop when he lived in Santa Maria. "The surrounding rock is medium to coarse grained sandstone with typical shallow water species such as Astrodapsis and massive Crassostrea titan which occurs in situ, upright instead of flat-lying like mst oysters. The ophiuroids are so dense that the 1-2 foot thick layer could be described as a sandy limestone; some of the lime cementing the grains is redeposited from the ophiuroid tests. The ophiuroid layer includes larger starfish, up to 4 inches across, that have not been determined."

MPRI 0053, 0054, 0072 related references: Arnold, R. 1908. Description of a new brittle-star from the upper Miocene of the Santa Cruz Mountains, California. Proceedings of the U.S. National Museum 34:403-406; Aronson, R. B. 1987. Predation on fossil and Recent ophiuroids. Paleobiology, vol. 13, no. 2, pp. 187?192; Aronson, R. B. 1987. A murder mystery from the Mesozoic.??New Scientist, 8 October 1987, pp. 55?59; Aronson, R. B. 1989. A community?level test of the Mesozoic marine revolution theory. Paleobiology, vol. 15, no. 1, pp. 20?25; Aronson, R. B. 1989. Brittle-star beds: low-predation anachronisms in the British Isles. Ecology 70(4):856-865; Aronson, R. B. 1991. An octopus’s garden. Natural History 1991(2):30-37; Aronson, R. B. 1991. Predation, physical disturbance, and sublethal arm damage in ophiuroids: a Jurassic-Recent comparison. Marine Ecology Progress Series 74:91-97; Aronson, R. B. 1992. Biology of a scale?independent predator?prey interaction. Marine Ecology Progress Series, vol. 89, pp. 1?13. [Data on proportion of individuals bearing 1 or more regenerating arms in dense, fossil ophiuroid populations. Expanded list of "fossil dense, autochthonous, shallow?water brittlestar beds"]; Aronson, R. B. 2001. Durophagy in marine organisms. pp. 393-397 In D.E.G. Briggs & P.R. Crowther (eds.), Palaeobiology II. Blackwell Science Ltd, 583 pp.; Aronson, R. B. and D. B. Blake. 1997. Evolutionary paleoecology of dense ophiuroid populations. -- Paleontological Society Papers 3:107-119; Aronson, R. B. and C. A. Harms. 1985. Ophiuroids in a Bahamian saltwater lake: The ecology of a Paleozoic?like community. Ecology, vol. 66, no. 5, pp. 1472?1483; Aronson, R. B. and H.?D. Sues. 1987. The paleoecological significance of an anachronistic community. Pp. 355?366. In Predation: direct and indirect impacts on aquatic communities. [W. C. Kerfoot and A. Sih, eds.] University Press of New England, Hanover, NH; Aronson, R. B. and H.?D. Sues. 1988. The fossil record of brittlestar beds. Pp. 147?148. In Echinoderm Biology (Proc. 6th IEC, Victoria/23?28 August 1987), [R. D. Burke et al. (eds)] A. A. Balkema, Rotterdam; Blake, D. B. 1975. A new west American Miocene species of the modern Australian ophiuroid Ophiocrossota. Journal of Paleontology 49(3):501-507; Blake, D. B. and R. C. Allison. 1970. A new west American Eocene species of the Recent Australian ophiuroid Ophiocrossota. Journal of Paleontology 44(5):925-927; Hall, C.A. 1962. Evolution of the echinoid genus Astrodapsis. University of California Publications in Geological Sciences 40(2):47-180; Merriam, C.W. 1931. Notes on a brittle-star limestone from the Miocene of California. American Journal of Science 21:304-310.

MPRI 0068 Argentinaster bodenbenderi

MPRI 0068 The disk and parts of three arms of an ophiuroid and two arm tips of a starfish from the lower Middle Devonian Sica Sica Formation, near La Paz, Bolivia. The ophiuroid is tentatively identified as Argentinaster bodenbenderi? The asteroid arm fragments are not identifiable. Occurrence of Argentinaster in Bolivia is not mentioned in the literature, although there are some mentions of Silurian and Devonian stelleroids by Kozlowski (1923). Ahlfeld (1946), Ahlfeld & Braniša (1960) and Braniša (1965). Argentinaster is important to understanding the origins of the modern order Ophiurida (Haude 1995), and more specimens for study would be highly desirable.MPRI 0075 and 0076 Protaster stellifer

Two specimens of a protasterid ophiuroid, Middleport Shale, Silurian, Middleport, NY. MPRI 0075 acquired by purchase, and MPRI 0076 received as generous gift from Dan L. Cooper, Fairfield, OH. Labeled Palaeaster niagarensis, but P. niagarensis is an asteroid whereas these are ophiuroids. These are very similar to Protaster stellifer Ringueberg, 1886 (New genera and species of fossils from the Niagara Shales. Bulletin of the Buffalo Society of Natural Sciences 5(1):1-22 + plates 1-2). Ringueberg described three ophiuroids in this paper, and it appears from comparison of Ringueberg’s written descriptions to the plates that the numbering of figures 2 and 3 on plate 1 is reversed [for 2 read 3, and for 3 read 2]. The numbering in the figure captions is not reversed. This mix-up of the figure numbers was not mentioned by Schuchert (1915 p. 228). Brett & Taylor (1977) identify ophiuroids of this type in the Lewiston Member of the Rochester Shale as Protaster stellifer Ringueberg.MPRI 0039

MPRI 0039. Small lot of dried starfish that have abnormalities. These specimens are not fossils and are not yet photographed. A dealer in Australia culled these specimens from vast quantities of dried starfish that are sold for souvenirs and for decoration. The specimen that prompted making this acquisition has a very rare abnormality called "double ambulacral groove". The other abnormalities include 4-armed and 6-armed specimens of normally 5-armed species, and a specimen with a bifurcated ray. Studies of teratological specimens of starfish give clues into the underlying ground plan of starfish construction. Related literature: Hotchkiss, F.H.C. 1979. Case studies in the teratology of starfish. Proc. Acad. Nat. Sci. Phil. 131:137-157. Hotchkiss, F.H.C. 2000. On the number of rays in starfish. American Zoologist 40(3):340-354. Hotchkiss, F.H.C. 2000. Inferring the developmental basis of the sea star abnormality "double ambulacral groove" (Echinodermata: Asteroidea). Revista Chilena de Historia Natural 73:579-583. Munar, J. 1984. Anomalias en la simetria de los Asteroidea (Echinodermata). Casos observados en aguas de Mallorca. Bolleti de la Societat d'historia Natural de les Balears. 28:59-66. Zavodnik, D. 1995. Odd symmetrical and teratological Asteroidea of the Center for Marine Research (Rovinj, Croatia). Natura Croatica 4:151-161.

Fossil

Fossil